You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Another Republican President, Another Recession.

- Thread starter hanimmal

- Start date

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-joe-biden-business-health-6e758dc5e24320677e48f58cbfca37bf

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Joe Biden is wielding his weapon of last resort in the nation’s fight against COVID-19, as he champions vaccination requirements across the country in an effort to force the roughly 67 million unvaccinated American adults to roll up their sleeves.

It’s a tactic he never wanted to employ — and had ruled out before he took office — but one that he feels he was forced into by a stubborn slice of the public that has refused to get the lifesaving shots and jeopardized the lives of others and the nation’s economic recovery.

In coming weeks, more than 100 million Americans will be subject to vaccine requirements ordered by Biden — and his administration is encouraging employers to take additional steps voluntarily that would push vaccines on people or subject them to onerous testing requirements.

MORE ON THE PANDEMIC

Forcing people to do something they don’t want to do is rarely a winning political strategy. But with the majority of the country already vaccinated and with industry on his side, Biden has emerged as an unlikely advocate of browbeating tactics to drive vaccinations.

- – Can I get the flu and COVID-19 vaccines at the same time?

- – While US summer surge is waning, more mandates in the works

- – Eviction confusion, again: End of US ban doesn't cause spike

- – Flush with COVID-19 aid, schools steer funding to sports

Biden on Thursday takes that message to Chicago, where he will visit a suburban construction site run by Clayco, a large building firm that is set to announce a new vaccinate-or-test requirement for its workforce. The company is taking action weeks ahead of a forthcoming rule by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration that will require all employers with more than 100 employees to require that their staffs be vaccinated or face weekly testing for the coronavirus.

White House officials said Biden will encourage other businesses to follow suit, by taking action ahead of the OSHA rule and to go even further by requiring shots for their employees without offering a test-out option.

Biden is also set to meet with the CEO of United Airlines, Scott Kirby, whose company successfully implemented a vaccine mandate — with no option for workers to be tested instead. Less than 1% have failed to comply and risk termination.

But Biden’s mandates have “worked spectacularly well,” said Lawrence Gostin, a public health expert at Georgetown University’s law school. He added that the president’s rules have also had a “modeling effect” for cities, states and businesses. That’s what the White House intended.

U.S. officials began anticipating the need for a more forceful vaccination campaign by April, when the nation’s supply of shots began to outpace demand. But political conditions meant immediate steps to require shots would have likely proved counterproductive.

The idea of mandatory vaccination faced pushback from critics who argue it smacks of government overreach and takes away people’s rights to make their own medical decisions.

So first, officials engaged in a monthslong and multibillion-dollar education and incentives effort to persuade people to get the vaccines of their own accord.

It wasn’t enough.

By midsummer, the more transmissible delta variant of the virus was eroding months of health and economic progress and the rate of new vaccinations had slowed to a trickle. Biden’s strategy shifted from inducement to compulsion, with a slow, and deliberate heightening of vaccination restrictions.

“It’s a good political strategy, but it also is a good public health strategy, because once you have a lot of people that have already been vaccinated. then mandates become more acceptable,” said Gostin.

It started with a vaccination requirement for federal frontline health workers serving veterans in VA hospitals. Then the military, followed in steady succession by all healthcare workers reimbursed by the government, all federal workers, and then the more than 80 million Americans who work at mid- and large-size companies.

Nearly 100 million adult Americans were unvaccinated in July — a figure that has been cut by a third since federal, state and private-sector mandates have been imposed.

In conjunction with the president’s trip to Chicago, the White House was releasing a report outlining the early successes of vaccine mandates at driving up vaccination rates and the economic case for businesses and local governments to implement them. It points to everything from reduced employee hours to diminished restaurant reservations in areas with fewer vaccinations, not to mention markedly reduced instances of serious illness and death from the virus in areas with higher vaccination rates.

Millions of workers, the White House notes, say they are still unable to work due to pandemic-related effects, because their workplaces have been shuttered or reduced service, or because they’re afraid to work or can’t get child care.

“The evidence has been overwhelmingly clear that these vaccine mandates work,” said Charlie Anderson, director of economic policy and budget for the White House COVID-19 response team. “And so now, I think it’s a good time to lift up and say, ‘Now’s the time to move, if you haven’t yet.’”

While mandates are the ultimate tool to press Americans to get vaccinated, Biden has resisted — at least thus far — requiring shots or tests for interstate or international air travel, a move that legal experts say is within his powers. But officials said it was still under consideration.

“We have a track record, and I think it’s clear, that shows that we’re pulling available levers to require vaccinations,” said Jeff Zients, the White House COVID-19 coordinator. “And we’re not taking anything off the table.”

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-business-congress-mitch-mcconnell-6e330d9fb94b73787ea70e7807b87151

WASHINGTON (AP) — Senate leaders announced an agreement Thursday to extend the government’s borrowing authority into December, temporarily averting an unprecedented federal default that experts say would have devastated the economy.

“Our hope is to get this done as soon as today,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer declared as he opened the Senate.

In their agreement, Republican and Democratic leaders edged back from a perilous standoff over lifting the nation’s borrowing cap, with Democratic senators accepting an offer from Senate GOP leader Mitch McConnell.

McConnell made the offer a day earlier just before Republicans were prepared to block longer-term legislation to suspend the debt limit and as President Joe Biden and business leaders ramped up their concerns that a default would disrupt government payments to millions of people and throw the nation into recession.

The Senate leaders had worked into the night hammering out the details.

“The Senate is moving forward,” McConnell said Thursday.

Wall Street continued to rally on the news. The S&P 500 rose 1.5% by midday, and the Nasdaq composite, with a heavy weighting of technology stocks, rose 1.8%.

The agreement sets the stage for a sequel of sorts in December, when Congress will again face pressing deadlines to fund the government and raise the debt limit before heading home for the holidays.

The agreement will allow for raising the debt ceiling by about $480 billion, according to a Senate aide familiar with the negotiations who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss them. That is the level that the Treasury Department has said is needed to get to Dec. 3.

“Basically, I’m glad that Mitch McConnell finally saw the light,” Bernie Sanders, the independent senator from Vermont, said late Wednesday. The Republicans “have finally done the right thing and at least we now have another couple months in order to get a permanent solution.”

Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Conn., added that, assuming final details in the emergency legislation are in order, “for the next three months, we’ll continue to make it clear that we are ready to continue to vote to pay our bills and Republicans aren’t.”

Unsurprisingly, McConnell portrayed it differently.

“The pathway our Democratic colleagues have accepted will spare the American people any near-term crisis, while definitively resolving the majority’s excuse that they lacked time to address the debt limit through (reconciliation),” McConnell said Thursday. “Now there will be no question: They’ll have plenty of time.”

Congress has just days to act before the Oct. 18 deadlinewhen the Treasury Department has warned it would quickly run short of funds to handle the nation’s already accrued debt load.

McConnell and Senate Republicans have insisted that Democrats would have to go it alone to raise the debt ceiling and allow the Treasury to renew its borrowing so that the country could meet its financial obligations. Further, McConnell has insisted that Democrats use the same cumbersome legislative process called reconciliation that they used to pass a $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief bill and have been employing to try to pass Biden’s $3.5 trillion measure to boost safety net, health and environmental programs.

McConnell said in his offer Wednesday that Republicans would still insist that Democrats use the reconciliation process for a long-term debt limit extension. However, he said Republicans are willing to “assist in expediting” that process, and in the meantime Democrats may use the normal legislative process to pass a short-term debt limit extension with a fixed dollar amount to cover current spending levels into December.

While he continued to blame Democrats, his offer will also allow Republicans to avoid the condemnation they would have gotten from some quarters if a financial crisis were to occur.

Earlier Wednesday, Biden enlisted top business leaders to push for immediately suspending the debt limit, saying the approaching deadline created the risk of a historic default that would be like a “meteor” that could crush the economy and financial markets.

At a White House event, the president shamed Republican senators for threatening to filibuster any suspension of the $28.4 trillion cap on the government’s borrowing authority. He leaned into the credibility of corporate America — a group that has traditionally been aligned with the GOP on tax and regulatory issues — to drive home his point as the heads of Citi, JP Morgan Chase and Nasdaq gathered in person and virtually to say the debt limit must be lifted.

“It’s not right and it’s dangerous,” Biden said of the resistance by Senate Republicans.

His moves came amid talk that Democrats might try to change Senate filibuster rules to get around Republicans. But Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., reiterated his opposition to such a change Wednesday, likely taking it off the table for Democrats.

The business leaders echoed Biden’s points about needing to end the stalemate as soon as possible, though they sidestepped the partisan tensions in doing so. Each portrayed the debt limit as an avoidable crisis.

“We just can’t wait to the last minute to resolve this,” said Jane Fraser, CEO of the bank Citi. “We are, simply put, playing with fire right now, and our country has suffered so greatly over the last few years. The human and the economic cost of the pandemic has been wrenching, and we don’t need a catastrophe of our own making.”

Ahead of the White House meeting, the administration warned that if the borrowing limit isn’t extended, it could set off an international financial crisis the United States might not be able to manage.

“A default would send shock waves through global financial markets and would likely cause credit markets worldwide to freeze up and stock markets to plunge,” the White House Council of Economic Advisers said in a new report. “Employers around the world would likely have to begin laying off workers.”

The recession that could be triggered could be worse than the 2008 financial crisis because it would come as many nations are still struggling with the COVID-19 pandemic, the report said.

Once a routine matter, raising the debt limit has become politically treacherous over the past decade or more, used by Republicans, in particular, to rail against government spending and the rising debt load.

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-business-congress-mitch-mcconnell-bills-e444072fb3b2f7d5a02793bf48d9ae96

WASHINGTON (AP) — In the frantic bid to avert a default on the nation’s debt, Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell held a position of unusual power — as the one who orchestrated both the problem and the solution.

McConnell is no longer the majority leader, but he is exerting his minority status in convoluted and uncharted ways, all in an effort to stop President Joe Biden’s domestic agenda and even if doing so pushes the country toward grave economic uncertainty.

All said, the outcome of this debt crisis leaves zero confidence there won’t be a next one. In fact, McConnell engineered an end to the standoff that ensures Congress will be in the same spot in December when funding to pay America’s bills next runs out. That means another potentially devastating debt showdown, all as the COVID-19 crisis lingers and the economy struggles to recover.

“Mitch McConnell loves chaos,” said Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, chairman of the Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee. “He’s a very smart tactician and strategist, but the country pays the price so often for what he does.”

The crisis has cemented McConnell’s legacy as a master of misdirection. He’s the architect of the impasse and the one who resolved it, if only for the short term. More battles are to come as Democrats narrow Biden’s big agenda, a now-$2 trillion expansion of health, child care and climate change programs, all paid for with taxes on corporations and the wealthy that Republicans oppose.

To some Republicans, McConnell is a shrewd leader, using every tool at his disposal to leverage power and undermine Biden’s priorities. To others, including Donald Trump, he is weak, having “caved” too soon. To Democrats, McConnell remains an infuriating rival who has shown again he is willing to break one institutional norm after another to pursue Republican power.

“McConnell’s role is to be the leader of the opposition and it’s his job to push back on what the majority wants to do,” said Alex Conant, a Republican strategist.

“Nobody should be surprised to see the leader of the Republicans making the Democrats’ job harder,” he said.

The risks are clear, not just for Biden and the Democrats who control Washington.

The debt showdown left Democrats portrayed as big spenders, willing to boost the nation’s now-$28.4 trillion debt to pay the bills. But both parties have contributed to that load because of past decisions that leave the government rarely operating in the black.

Republicans, too, risk recriminations from all sides of their deeply divided party. In easing off the crisis, McConnell insulated his Republicans from further blame, but infuriated Trump and his allies, who are eager to skewer the Kentucky senator for giving in.

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, said he told his colleagues during a private meeting before the debt vote that it was “a mistake for Republican leadership to agree to this deal.”

Once a routine vote to ensure the nation’s bills are paid, raising the debt limit has become a political weapon, particularly for Republicans, to rail against government spending. The tea party class of Republicans a decade ago brought the nation to the brink of default over the issue and set a new GOP strategy.

In this case, McConnell made it clear he had no demands other than to disrupt Biden’s domestic agenda, the now-$2 trillion package that is the president’s signature legislation but is derided by Republicans as a “socialist tax-and-spending spree.”

In muscling Biden’s agenda to passage, Democrats are relying on a complicated procedure, the budget reconciliation process, which allows 51 votes for approval, rather than the 60 typically needed to overcome Senate objections. In the 50-50 split Senate, Vice President Kamala Harris gives Democrats the majority with her ability to cast a tiebreaking vote.

McConnell seized on the Democratic budget strategy as a way to conflate the issues, announcing months ago he wanted Democrats to increase the debt limit on their own using the same procedure. It was his way of linking Biden’s big federal government overhaul with the nation’s rising debt load, even though they are separate and most of Biden’s agenda hasn’t been enacted.

The debt raising vote has rarely been popular, and both parties have had to do it on their own, at times. But McConnell struck new legislative ground trying to dictate the terms to Democrats.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., promptly ignored McConnell’s demands for the cumbersome process, and set out to pass the debt ceiling bill with a more traditional route.

As the Oct. 18 deadline approached, when Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned the government would run out of funds to pay the nation’s bills, Schumer’s strategy hit the Republican blockade, or filibuster. Only after business pressure mounted and Biden implored Republicans to “get out of the way” did McConnell call a time out.

McConnell orchestrated the way around the problem by allowing the traditional vote on Thursday night and even joining 10 other Republican senators in helping Democrats reach the 60-vote threshold needed to ease off the crisis.

White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki lauded the Republicans who “did their part tonight, ending the filibuster and allowing Democrats to do the work of raising the debt limit.” But she urged the parties to come together to find a more permanent solution.

“We can’t allow the routine process of paying our bills to turn into a confidence-shaking political showdown every two years or every two months,” she said.

Schumer struck a more acerbic tone.

“Republicans played a dangerous and risky partisan game, and I am glad that their brinkmanship did not work,” he said.

That, too, brought trouble: McConnell said in letter to Biden late Friday that such antics assure “I will not provide such assistance again.”

That night before voting, McConnell told Republican colleagues that he devised the solution in part because he was worried that Democrats would change the filibuster rules, as they had been discussing as an option of last resort. He had reached out to two key Democrats, Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Sen. Kyrsten of Arizona, to ensure they weren’t thinking of doing that.

And besides, the Republican leader had accomplished his goal: jamming up Biden’s agenda, sowing the seeds of fiscal distress and portraying Democrats as a party struggling to govern.

It’s the first big fight that McConnell has picked with Biden, and it appears to be the one that could define the final phase of their decadeslong association.

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-business-congress-bills-financial-markets-9abe4ef546f62521bcfe7dc3c9517eaf

WASHINGTON (AP) — Members of the House are scrambling back to Washington on Tuesday to approve a short-term lift of the nation’s debt limit and ensure the federal government can continue fully paying its bills into December.

The $480 billion increase in the country’s borrowing ceiling cleared the Senate last week on a party-line vote. The House is expected to approve it swiftly so President Joe Biden can sign it into law this week. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen had warned that steps to stave off a default on the country’s debts would be exhausted by Monday, and from that point, the department would soon be unable to fully meet the government’s financial obligations.

A default would have immense fallout on global financial markets built upon the bedrock of U.S. government debt. Routine government payments to Social Security beneficiaries, disabled veterans and active-duty military personnel would also be called into question.

“It is egregious that our nation has been put in this spot, but we must take immediate action to address the debt limit and ensure the full faith and credit of the United States remains intact,” said House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, D-Md.

FULL COVERAGE

GOP's Poliquin to decamp from coastal home to Bangor area

House returns to stave off default with debt limit vote

Risky move: Biden undercuts WH executive privilege shield

Michigan redistricting panel advances maps to hearing stage

But the relief provided by the bill’s passage will only be temporary, forcing Congress to revisit the issue in December — a time when lawmakers will also be laboring to complete federal spending bills and avoid a damaging government shutdown. The yearend backlog raises risks for both parties and threatens a tumultuous close to Biden’s first year in office.

The present standoff over the debt ceiling eased when Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., agreed to help pass the short-term increase. But he insists he won’t do so again.

In a letter sent Friday to Biden, McConnell said Democrats will have to handle the next debt-limit increase on their own using the same process they have tried to use to pass Biden’s massive social spending and environment plan. Reconciliation allows legislation to pass the Senate with 51 votes rather than the 60 that’s typically required. In the 50-50 split Senate, Vice President Kamala Harris gives Democrats the majority with her tiebreaking vote.

In his focus on the debt limit, McConnell has tried to link Biden’s big federal government spending boost with the nation’s rising debt load, even though they are separate and the debt ceiling will have to be increased or suspended regardless of whether Biden’s $3.5 trillion plan makes it into law.

“Your lieutenants on Capitol Hill now have the time they claimed they lacked to address the debt ceiling through standalone reconciliation, and all the tools to do it,” McConnell said in the letter. “They cannot invent another crisis and ask for my help.”

McConnell was one of 11 Republicans who sided with Democrats to advance the debt ceiling reprieve to a final vote. Subsequently, McConnell and his GOP colleagues voted against final passage.

Agreement on a short-term fix came abruptly. Some Republican senators said threats from Democrats to eliminate the 60-vote threshold for debt ceiling votes — Biden called it a “real possibility” — had played a role in McConnell’s decision.

“I understand why Republican leadership blinked, but I wish they had not,” said Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas.

The current debt ceiling is $28.4 trillion. Both parties have contributed to that load with decisions that have left the government rarely operating in the black.

The calamitous ramifications of default are why lawmakers have been able to reach a compromise to lift or suspend the debt cap some 18 times since 2002, often after frequent rounds of brinkmanship.

“Global financial markets and the economy would be upended, and even if resolved quickly, Americans would pay for this default for generations,” warned a recent report from Moody’s Analytics.

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://apnews.com/article/social-security-cola-increase-4f2cd7b763371b91923227be883e367e

WASHINGTON (AP) — Millions of retirees on Social Security will get a 5.9% boost in benefits for 2022. The biggest cost-of-living adjustment in 39 years follows a burst in inflation as the economy struggles to shake off the drag of the coronavirus pandemic.

The COLA, as it’s commonly called, amounts to $92 a month for the average retired worker, according to estimates released Wednesday by the Social Security Administration. That marks an abrupt break from a long lull in inflation that saw cost-of-living adjustments averaging just 1.65% a year over the past 10 years.

With the increase, the estimated average Social Security payment for a retired worker will be $1,657 a month next year. A typical couple’s benefits would rise by $154 to $2,753 per month.

POLITICS

FDA spells out lower sodium goals for food industry

Aim to ease supply chain bottlenecks with LA port going 24/7

US talks global cybersecurity without a key player: Russia

US to reopen land borders in November for fully vaccinated

'Difficult decisions' as Biden, Democrats shrink plan to $2T

But that’s just to help make up for rising costs that recipients are already paying for food, gasoline and other goods and services.

“It goes pretty quickly,” retiree Cliff Rumsey said of the cost-of-living increases he’s seen. After a career in sales for a leading steel manufacturer, Rumsey lives near Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. He cares at home for his wife of nearly 60 years, Judy, who has advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Since the coronavirus pandemic, Rumsey said he has also noted price increases for wages paid to caregivers who occasionally spell him and for personal care products for Judy.

The COLA affects household budgets for about 1 in 5 Americans. That includes Social Security recipients, disabled veterans and federal retirees, nearly 70 million people in all. For baby boomers who embarked on retirement within the past 15 years, it will be the biggest increase they’ve seen.

Among them is Kitty Ruderman of Queens in New York City, who retired from a career as an executive assistant and has been collecting Social Security for about 10 years. “We wait to hear every year what the increase is going to be, and every year it’s been so insignificant,” she said. “This year, thank goodness, it will make a difference.”

Ruderman says she times her grocery shopping to take advantage of midweek senior citizen discounts, but even so price hikes have been “extreme.” She says she doesn’t think she can afford a medication that her doctor has recommended.

AARP CEO Jo Ann Jenkins called the government payout increase “crucial for Social Security beneficiaries and their families as they try to keep up with rising costs.”

Policymakers say the COLA was designed as a safeguard to protect Social Security benefits against the loss of purchasing power, and not a pay bump for retirees. About half of seniors live in households where Social Security benefits provide at least 50% of their income, and one-quarter rely on their monthly payment for all or nearly all their income.

“Regardless of the size of the COLA, you never want to minimize the importance of the COLA,” said retirement policy expert Charles Blahous, a former public trustee helping to oversee Social Security and Medicare finances. “What people are able to purchase is very profoundly affected by the number that comes out. We are talking the necessities of living in many cases.”

This year’s Social Security trustees report amplified warnings about the long-range financial stability of the program, but there’s little talk about fixes in Congress with lawmakers’ attention consumed by President Joe Biden’s massive domestic legislation and partisan machinations over the national debt. Social Security cannot be addressed through the budget reconciliation process Democrats are attempting to use to deliver Biden’s promises.

Social Security’s turn will come, said Rep. John Larson, D-Conn., chairman of the House Social Security subcommittee and author of legislation to tackle shortfalls that would leave the program unable to pay full benefits in less than 15 years. His bill would raise payroll taxes while also changing the COLA formula to give more weight to health care expenses and other costs that weigh more heavily on the elderly. Larson said he intends to press ahead next year.

“This one-time shot of COLA is not the antidote,” he said.

Although Biden’s domestic package includes a major expansion of Medicare to cover dental, hearing and vision care, Larson said he hears from constituents that seniors are feeling neglected by the Democrats.

“In town halls and tele-town halls they’re saying, ‘We are really happy with what you did on the child tax credit, but what about us?’” Larson added. “In a midterm election, this is a very important constituency.”

The COLA is only one part of the annual financial equation for seniors. An announcement about Medicare’s Part B premium for outpatient care is expected soon. It’s usually an increase, so at least some of any Social Security raise goes for health care. The Part B premium is now $148.50 a month, and the Medicare trustees report estimated a $10 increase for 2022.

Economist Marilyn Moon, who also served as public trustee for Social Security and Medicare, said she believes the current spurt of inflation is an adjustment to highly unusual economic circumstances and the pattern of restraint on prices will reassert itself with time.

“I would think there is going to be an increase this year that you won’t see reproduced in the future,” Moon said.

Policymakers should not delay getting to work on retirement programs, she said.

“We’re at a point in time where people don’t react to policy needs until there is a sense of desperation, and both Social Security and Medicare are programs that benefit from long-range planning rather short-range machinations,” she said.

Social Security is financed by payroll taxes collected from workers and their employers. Each pays 6.2% on wages up to a cap, which is adjusted each year for inflation. Next year the maximum amount of earnings subject to Social Security payroll taxes will increase to $147,000.

The financing scheme dates to the 1930s, the brainchild of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who believed a payroll tax would foster among average Americans a sense of ownership that would protect the program from political interference.

That argument still resonates. “Social Security is my lifeline,” said Ruderman, the New York retiree. “It’s what we’ve worked for.”

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://apnews.com/article/business-prices-inflation-28e1231bdb445d482bb2d2e25dff1983

NEW YORK (AP) — Get ready to pay sharply higher bills for heating this winter, along with seemingly everything else.

With prices surging worldwide for heating oil, natural gas and other fuels, the U.S. government said Wednesday it expects households to see their heating bills jump as much as 54% compared to last winter.

Nearly half the homes in the U.S. use natural gas for heat, and they could pay an average $746 this winter, 30% more than a year ago. Those in the Midwest could get particularly pinched, with bills up an estimated 49%, and this could be the most expensive winter for natural-gas heated homes since 2008-2009.

The second-most used heating source for homes is electricity, making up 41% of the country, and those households could see a more modest 6% increase to $1,268. Homes using heating oil, which make up 4% of the country, could see a 43% increase — more than $500 — to $1,734. The sharpest increases are likely for homes that use propane, which account for 5% of U.S. households.

This winter is forecast to be slightly colder across the country than last year. That means people will likely be burning more fuel to keep warm, on top of paying more for each bit of it. If the winter ends up being even colder than forecast, heating bills could be higher than estimated, and vice-versa.

The forecast from the U.S. Energy Information Administration is the latest reminder of the higher inflation ripping across the global economy. Earlier Wednesday, the government released a separate report showing that prices were 5.4% higher for U.S. consumers in September than a year ago. That matches the hottest inflation rate since 2008, as a reawakening economy and snarled supply chains push up prices for everything from cars to groceries.

BUSINESS

Biden tries to tame inflation by having LA port open 24/7

From cars to gasoline, surging prices match a 13-year high

Social Security checks getting big boost as inflation rises

Winter heating bills set to jump as inflation hits home

The higher prices hit everyone, with pay raises for most workers so far failing to keep up with inflation. But they hurt low-income households in particular.

“After the beating that people have taken in the pandemic, it’s like: What’s next?” said Carol Hardison, chief executive officer at Crisis Assistance Ministry, which helps people in Charlotte, North Carolina, who are facing financial hardship.

She said households coming in for assistance recently have had unpaid bills that are roughly twice as big as they were before the pandemic. They’re contending with more expensive housing, higher medical bills and sometimes a reduction in their hours worked.

“It’s what we know about this pandemic: It’s hit the same people that were already struggling with wages not keeping up with the cost of living,” she said.

To make ends meet, families are cutting deeply. Nearly 22% of Americans had to reduce or forego expenses for basic necessities, such as medicine or food, to pay an energy bill in at least one of the last 12 months, according to a September survey by the U.S. Census Bureau.

“This is going to create significant hardship for people in the bottom third of the country,” said Mark Wolfe, executive director of the National Energy Assistance Directors’ Association. “You can tell them to cut back and try to turn down the heat at night, but many low-income families already do that. Energy was already unaffordable to them.”

Many of those families are just now getting through a hot summer where they faced high air-conditioning bills.

Congress apportions some money to energy assistance programs for low-income households, but directors of those programs are now watching their purchasing power shrink as fuel costs keep climbing, Wolfe said.

The biggest reason for this winter’s higher heating bills is the recent surge in prices for energy commodities after they dropped to multi-year lows in 2020. Demand has simply grown faster than production as the economy roars back to life following shutdowns caused by the coronavirus.

Natural gas in the United States, for example, has climbed to its highest price since 2014 and is up roughly 90% over the last year. The wholesale price of heating oil, meanwhile, has more than doubled in the last 12 months.

Another reason for the rise is how global the market for fuels has become. In Europe, strong demand and limited supplies have sent natural gas prices up more than 350% this year. That’s pushing some of the natural gas produced in the United States to head for ships bound for other countries, adding upward pressure on domestic prices as well.

The amount of natural gas in storage inventories is relatively low, according to Barclays analyst Amarpreet Singh. That means there’s less of a cushion heading into winter heating season.

Heating oil prices, meanwhile, are tied closely to the price of crude oil, which has climbed more than 60% this year. Homes affected by those increases are primarily in the Northeast, where the percentage of homes using heating oil has dropped to 18% from 27% over the past decade.

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://apnews.com/article/wildfires-floods-climate-change-joe-biden-science-6a24aa24e1cc4fcb03a6bda6f364375a

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Biden administration is taking steps to address the economic risks from climate change, issuing a 40-page report Friday on government-wide plans to protect the financial, insurance and housing markets and the savings of American families.

The report lays out steps that could potentially alter the mortgage process, stock market disclosures, retirement plans, federal procurement and government budgeting.

It’s a follow-up to a May executive order by President Joe Biden that essentially calls on the government to analyze how the world’s largest economy could be affected by extreme heat, flooding, storms, wildfires and the broader adjustments needed to address climate change.

“If this year has shown us anything, it’s that climate change poses an ongoing urgent and systemic risk to our economy and to the lives and livelihoods of everyday Americans, and we must act now,” Gina McCarthy, the White House national climate adviser, told reporters.

A February storm in Texas led to widespread power outages, 210 deaths and severe property damage. Wildfires raged in Western states. The heat dome in the Pacific Northwest caused record temperatures in Seattle and Portland, Oregon. Hurricane Idastruck Louisiana in August and caused deadly flooding in the Northeast.

CLIMATE CHANGE

3 German parties aim to start formal coalition talks

White House targeting economic risks from climate change

British queen appears to show irritation at climate inaction

Australian prime minister will attend Glasgow climate talks

The actions being recommended by the Biden administration reflect a significant shift in the broader discussion about climate change, suggesting that the nation must prepare for the costs that families, investors and governments will bear.

The report is also an effort to showcase to the world how serious the U.S. government is about tackling climate change ahead of the United Nations Climate Change Conferencerunning from Oct. 31 to Nov. 12 in Glasgow, Scotland.

Among the steps outlined is the government’s Financial Stability Oversight Council developing the tools to identify and lessen climate-related risks to the economy. The Treasury Department plans to address the risks to the insurance sector and availability of coverage. The Securities and Exchange Commission is looking at mandatory disclosure rules about the opportunities and risks generated by climate change.

The Labor Department on Wednesday proposed a rule for investment managers to factor environmental decisions into the choices made for pensions and retirement savings. The Office of Management and Budget announced the government will begin the process of asking federal agencies to consider greenhouse gas emissions from the companies providing supplies. Biden’s budget proposal for fiscal 2023 will feature an assessment of climate risks.

Federal agencies involved in lending and mortgages for homes are looking for the impact on the housing market, with the Department of Housing and Urban Development and its partners developing disclosures for homebuyers and flood and climate-related risks. The Department of Veterans Affairs will also look at climate risks for its home lending program.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is updating the standards for its National Flood Insurance Program, potentially revising guidelines that go back to 1976.

“We now do recognize that climate change is a systemic risk,” McCarthy said. “We have to look fundamentally at the way the federal government does its job and how we look at the finance system and its stability.”

CatHedral

Well-Known Member

Dealing with climate change will be ruinously expensive.

Not dealing with it will be many times worse.

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/10/14/inflation-prices-supply-chain/

The bumpy economic recovery has had policymakers, economists and Americans at large grappling with greater price hikes for groceries, gas, cars, rent and just about everything else we need.

For months, officials at the Federal Reserve and White House have argued that pandemic-era inflation is temporary, or “transitory,” and that prices will simmer back down as the economy has time to heal. The hope was that inflation would have started cooling down by now.

But the delta variant of the coronavirus and the persistent supply chain backlogs have kept prices elevated. There is no clear answer for when that will change, leaving Americans to feel the strain in their pocketbooks in the meantime. This is a breakdown of how we got here.

Policymakers were encouraged when August prices eased slightly, breaking an eight-month streak of rising or steady inflation. But September reversed course, coming in at 5.4 percent compared to the year before, in large part due to the rapidly spreading delta variant stifling the recovery.

Economists caution against drawing too much from one month of data, good or bad. But the overall picture increasingly suggests that inflation is sticking around longer than economic policymakers at the Fed and White House anticipated just a few months ago. Fed Chair Jerome Powell told lawmakers last month that the supply-side constraints on the economy have, “in some cases, gotten worse,” adding that "we need those supply blockages to alleviate, to abate before inflation can come down.”

One Fed official is even ditching the word “transitory” altogether, saying it hands the public a false sense of hope that this will pass in a shorter time frame. Meanwhile, the Biden administration announced a 24/7 operation at a key U.S. port this week and is working with major importers to clear a path for cargo ahead of crunch time during the holiday season.

Policymakers often argue that price increases are limited to industries like hotels, airlines and cars. But federal data on Wednesday pointed to food and shelter costs rising in September, together contributing to more than half of the monthly increase of all items, when seasonally adjusted.

The concerns over soaring home prices and rising rents have economists worried about whether cost increases will last even after the pandemic has mostly passed. The still hot housing market has made it that much more difficult for first-time buyers, or those without cash or solid credit, to buy a home. Meanwhile, rising rents in major metropolitan areas are pushing out more people who are now wondering if they can afford to stay.

On top of it all, an energy crisis has ricocheted through the supply chains. According to AAA, the national average for a gallon of gas on Thursday was $3.29, up from $3.17 one month ago, and $2.18 one year ago.

Throughout the pandemic, new and used cars have been a kind of litmus test for the country’s supply chain issues and related price hikes. Used cars and trucks have been a driving force behind the surge in inflation this year, up a whopping 52 percent since fall 2019, before the pandemic.

The market relies heavily on trade-ins and auto parts, which have been in low supply amid a global microchip shortage. That pinch has made it more expensive for dealers to get any of their models, much less repair them. All of those problems are also hurting the supply of used cars, which depend on trade ins as well as rental car company inventories.

Meanwhile, the pandemic triggered a massive rental car shortage after a slew of large companies sold off hundreds of thousands of models that sat idle at the start of the pandemic as Americans stopped traveling. Back in May of this year, more than one of every three rental cars that had been in service before the pandemic was no longer available.

However, as more people got vaccinated and started itching for spring and summer trips, customer demand boomed. Companies could not get their hands on cars fast enough, driving up prices while people scrambled for reservations and companies rushed to restock lots.

New cars are now also seeing rising prices thanks to the ongoing microchip shortage. Pandemic-related shutdowns have pinched factories around the world. For instance, auto production in North America has been slowed by shutdowns in countries like Malaysia and Vietnam.

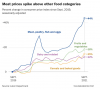

Families across the nation are also facing higher prices at the grocery store, which have people stretching their wallets for dairy, fruits and vegetables, baked goods and meats. Prices for meat, poultry, fish and eggs have surged in particular above other grocery categories. The White House has pointed to broad consolidation in the meat industry, saying that large companies bear some of the responsibility for pushing prices higher.

Meat industry groups disagree, arguing that the same supply-side issues rampant in the rest of the economy apply to proteins because it costs more to transport and package materials, while labor shortages have held back meat production. Meanwhile, food categories with less of a surge are still seeing prices tick up while supply chains lag. The September consumer price index showed apples up 3.8 percent compared to August. Peanut butter was up 3.0 percent, and potatoes were up 2.4 percent.

Where do we go from here?

Looming in the background is another major challenge for policymakers, which is how to keep inflation expectations in check. There is an inherent psychological aspect to inflation: If consumers or businesses expect the cost of goods and services to keep rising, they may change their behavior now. For instance, vacationers might rush to book hotel rooms now. Or businesses may stock up on advance orders, pushing prices higher and making those very expectations self-fulfilling events.

Fed leaders say they are not worried and would respond if they started to see concerning signs bubble up. But some measures suggest anxiety is high. One survey of consumer inflation expectations tracked by the New York Fed hit a record high in September. Consumer confidence took a tumble in August as the delta variant spread across the country, according to a closely tracked survey which is run by the University of Michigan. “There is little doubt that the pandemic’s resurgence due to the delta variant has been met with a mixture of reason and emotion,” the survey results said.

hanimmal

Well-Known Member

https://apnews.com/article/business-iowa-nebraska-d95ef3d2aee8e80aa5aca6d06ffa50a4

DES MOINES, Iowa (AP) — Like other ranchers across the country, Rusty Kemp for years grumbled about rock-bottom prices paid for the cattle he raised in central Nebraska, even as the cost of beef at grocery stores kept climbing.

He and his neighbors blamed it on consolidation in the beef industry stretching back to the 1970s that resulted in four companies slaughtering over 80% of the nation’s cattle, giving the processors more power to set prices while ranchers struggled to make a living. Federal data show that for every dollar spent on food, the share that went to ranchers and farmers dropped from 35 cents in the 1970s to 14 cents recently.

It led Kemp to launch an audacious plan: Raise more than $300 million from ranchers to build a plant themselves, putting their future in their own hands.

“We’ve been complaining about it for 30 years,” Kemp said. “It’s probably time somebody does something about it.”

Crews will start work this fall building the Sustainable Beef plant on nearly 400 acres near North Platte, Nebraska, and other groups are making similar surprising moves in Iowa, Idaho and Wisconsin. The enterprises will test whether it’s really possible to compete financially against an industry trend that has swept through American agriculture and that played a role in meat shortages during the coronavirus pandemic.

BUSINESS

Backlog in federal safety rules amid US car crash ‘epidemic’

Bitcoin-mining power plant raises ire of environmentalists

Unhappy with prices, ranchers look to build own meat plants

New skyscraper lab will test elevators high above Atlanta

The move is well timed, as the U.S. Department of Agriculture is now taking a number of steps to encourage a more diverse supply in the beef industry.

Still, it’s hard to overstate the challenge, going up against huge, well-financed competitors that run highly efficient plants and can sell beef at prices that smaller operators will struggle to match.

The question is whether smaller plants can pay ranchers more and still make a profit themselves. An average 1,370-pound steer is worth about $1,630, but that value must be divided between the slaughterhouse, feed lot and the rancher, who typically bears the largest expense of raising the animal for more than a year.

David Briggs, the CEO of Sustainable Beef, acknowledged the difficulty but said his company’s investors remain confident.

“Cattle people are risk takers and they’re ready to take a risk,” Briggs said.

Consolidation of meatpacking started in the mid-1970s, with buyouts of smaller companies, mergers and a shift to much larger plants. Census data cited by the USDA shows that the number of livestock slaughter plants declined from 2,590 in 1977 to 1,387 in 1992. And big processors gradually dominated, going from handling only 12% of cattle in 1977 to 65% by 1997.

Currently four companies — Cargill, JBS, Tyson Foods and National Beef Packing — control over 80% of the U.S. beef market thanks to cattle slaughtered at 24 plants. That concentration became problematic when the coronavirus infected workers, slowing and even closing some of the massive plants, and a cyberattack last summer briefly forced a shutdown of JBS plants until the company paid an $11 million ransom.

The Biden administration has largely blamed declining competition for a 14% increase in beef prices from December 2020 to August. Since 2016, the wholesale value of beef and profits to the largest processors has steadily increased while prices paid to ranchers have barely budged.

The backers of the planned new plants have no intention of replacing the giant slaughterhouses, such as a JBS plant in Grand Island, Nebraska, that processes about 6,000 cattle daily — four times what the proposed North Platte plant would handle.

However, they say they will have important advantages, including more modern equipment and, they hope, less employee turnover thanks to slightly higher pay of more than $50,000 annually plus benefits along with more favorable work schedules. The new Midwest plants are also counting on closer relationships with ranchers, encouraging them to invest in the plants, to share in the profits.

The companies would market their beef both domestically and internationally as being of higher quality than meat processed at larger plants.

Chad Tentinger, who is leading efforts to build a Cattlemen’s Heritage plant near Council Bluffs, Iowa, said he thinks smaller plants were profitable even back to the 1970s but that owners shifted to bigger plants in hopes of increasing profits.

Now, he said, “We want to revolutionize the plant and make it an attractive place to work.”

Besides paying ranchers more and providing dividends to those who own shares, the hope is that their success will spur more plants to open, and the new competitors will add openness to cattle markets.

Derrell Peel, an agricultural economist at Oklahoma State University, said he hopes they’re right, but noted that research shows even a 30% reduction in a plant’s size will make it far less efficient, meaning higher costs to slaughter each animal.

Unless smaller plants can keep expenses down, they will need to find customers who will pay more for their beef, or manage with a lower profit margin than the big companies.

“We have these very large plants because they’re extremely efficient,” Peel said.

According to the North American Meat Institute, a trade group that includes large and mid-size plants, the biggest challenge will be the shortage of workers in the industry.

It’s unfair to blame the big companies and consolidation for the industry’s problems, said Tyson Fresh Meats group president Shane Miller.

“Many processors, including Tyson, are not able to run their facilities at capacity in spite of ample cattle supply,” Miller told a U.S. Senate committee in July. “This is not by choice: Despite our average wage and benefits of $22 per hour, there are simply not enough workers to fill our plants.”

The proposed new plants come as the USDA is trying to increase the supply chain. The agency has dedicated $650 million toward funding mid-size and small meat and poultry plants and $100 million in loan guarantees for such plants. Also planned are new rules to label meat as a U.S. product to differentiate it from meat raised in other countries.

“We’re trying to support new investment and policies that are going to diversify and address that underlying problem of concentration,” said Andy Green, a USDA senior adviser for fair and competitive markets.